Secret Rocks

Secret Rocks

The $10 billion jewels industry is shrouded in beauty—and mystery. Is change about to come?

By Shibani Mahtani and Patrick Barta

The Wall Street Journal

TO HEAR RICHARD HUGHES tell it, the journey was like something straight out of “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.” One of the world’s leading modern-day gem hunters, he was hell-bent on reaching the fabled jade mines of upper Myanmar—a jungle redoubt so remote and closely guarded that few living Westerners have ever laid eyes on it.

But none of it could have prepared Hughes for what he found when he reached his destination three days later: a Wild West boomtown unlike anything he had ever seen. Stores were stocked with imported cognac and French perfume, while locals frittered away cash on roulette wheels, drugs and prostitutes. Fortune hunters tried just about anything to find jade—including diving into rivers with tubes hooked up to bicycle pumps onshore so they could breathe underwater. When people found dirty brown rocks they thought might contain jade, they thwacked them with hammers to see what kind of sound they made: If they rang like a bell, that was a good sign. In the main mines, meanwhile, armies of men marched along tracks hauling baskets filled with earth—more dirt, and perhaps more jade, from the depths below.

The Mysterious World of Gems

To Hughes, it was like stepping into the age of the pharaohs. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is like building the pyramids,'” he recalls.

Hughes’s inaugural journey to the Hpakant jade mines took place more than a decade and a half ago. But to a surprisingly large degree, Myanmar’s famed gem mines have remained untamed, according to more recent visitors. The same, it turns out, could be said of the entire $10 billion “colored” jewels industry, the storied but murky business centered around 50 or so colored gemstones, such as jade, rubies, emeralds and sapphires, which have entranced the world’s wealthy since the days of the Mughal dynasty and Catherine the Great.

Unlike the global diamond business, which is largely controlled by big companies like De Beers and painstakingly tracked by investors and Wall Street bankers, the colored gems world is still dominated by small miners and adventurers who wander some of the globe’s most dangerous or underdeveloped places in search of treasure. The best stones tend to come from countries like Madagascar, Tajikistan, Colombia and Myanmar, where smuggling often is rampant, record-keeping is poor, and mine owners are sometimes reluctant to let outsiders visit for fear they might cut their own deals with the locals.

In some cases, experts like Hughes buy up stones from miners or middlemen and resell them to rich clients. Other gems find their way to the public via wholesalers who pick them up at auctions or markets in Thailand, India and other processing centers. One auction in Myanmar in 2011 alone netted $2.8 billion in sales. Either way, gem buyers—from newlyweds to collectors to fashionistas, who gobble up stones in New York, London or just about anywhere else—rarely have any idea where their gems came from and might not be able to find out for sure if they wanted to. When it comes to tracking basic data about which countries are producing the most stones, the industry is “very vague,” says Jean Claude Michelou, a vice president at the International Colored Gemstone Association, a trade group.

Indeed, if you want to find the chief executive or major shareholders behind the best ruby or sapphire mines, good luck. In Myanmar, long considered the world’s most important source of rubies and jade, many mines are controlled by the military or its close associates, including some who are targeted by U.S. sanctions established years ago to punish the country’s harsh military regime. (Although many of those rules have been loosened over the past two years, since a new reformist government in Myanmar began rolling back decades of harsh military rule, some restrictions on new Myanmar stones remain.) But the stones can also come from private fortune seekers whose identities are largely unknown outside of their home bases. One of the gem tycoons Hughes met during his time in Hpakant was a former taxi driver who started out with a $23 boulder he bought from a passenger and then resold it for $5,000 to a jade trader. (When Hughes met the man in 1996, he posed for a photograph standing atop a pile of jade rocks that filled an entire room in his home.)

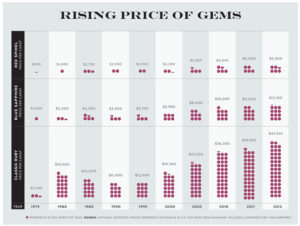

Still, while it’s hard to track the industry’s growth, experts say prices have climbed significantly in recent years, largely because supplies are erratic. Robert Genis, a Tucson-based gem hunter and dealer who got his start in the 1970s, says high-grade Myanmar rubies have quadrupled in retail value to more than $40,000 a carat since the mid-1990s, while Colombian emeralds have roughly doubled since a low in the early 2000s. Hughes, who has trekked across 30 or more countries for stones and now lives in Bangkok, says jade prices shot up 10-fold over the past five years, due largely to surging demand in China, though prices have eased recently.

And for people willing to hold on to their stones for a long time—or generations—the returns can be enormous. Consider the 62-carat Rockefeller Sapphire once owned by John D. Rockefeller Jr., who bought it from an Indian maharajah in 1934 and had it redesigned as a brooch for his wife. The family sold the stone in 1971 to a famous gem dealer for $170,000. Nine years later, it went on the block again and was sold for $1.5 million, and then resold for more than $3 million in 2001. Another famous sapphire, bought by 19th-century industrialist James J. Hill in the 1880s for his wife for $2,200, sold for just over $3 million at auction in 2007. And of course, there’s the so-called Elizabeth Taylor Ruby, an 8-carat stone from Myanmar that was given to the late Hollywood star by Richard Burton in 1968 as a Christmas gift. In 2011, it was auctioned off for $4.2 million.

DIAMONDS ARE OF COURSE a lady’s best friend, but colored gems continue to have a mystical allure that even the king of jewelry can’t claim. Part of the romance is tied to the stones’ luminous beauty and scarcity. For many wealthy people, especially in Asia, there’s nothing quite like having a bag of shiny stones they can carry around or stash away—and sell—in case of emergency. That has become even truer since the global financial crisis, which left many affluent people hungry for alternative ways of storing wealth.

It doesn’t hurt that colored stones come with such atmospheric histories, making them all the more addictive. The Mughal dynasty, whose emperors included Shah Jahan, builder of the Taj Mahal, had its famous Peacock Throne inlaid with rubies and other precious stones. Chinese leaders were known to favor jade as far back as 3000 B.C., while Russians placed a roughly 400-carat red spinel, believed to date back to the 1400s, in their imperial crown. More recently, Prince William gave Kate Middleton a sapphire engagement ring that had belonged to his mother, Princess Diana.

Finding big new stones to quench the world’s demand, though, isn’t easy. That’s where gem hunters come in. Genis, the Tucson-based dealer, says he got started in college, when he pulled out maps to see where the world’s most coveted natural resources, including tin, gold and copper, were located. It was a tiny green symbol on Colombia, depicting emerald deposits, that captivated him the most. He sold his stereo and a secondhand car to scrape together $1,000 for his journey. “I knew I did not want to come back broke,” Genis says.

After a bus ride to California’s border with Mexico, some trains and some hitchhiking, Genis landed in Bogota’s emerald district and spent his remaining cash on gems. Back in the U.S., he doubled his money selling the stones. “Suddenly I had $1,000 more, and I thought, ‘Hey, this is much better than going to school,'” he recalls. After repeat visits, he was making enough to fly to Colombia instead of taking the bus, with stops for fun in the Caribbean on the way home.

These days, Genis trusts other people to find many of the stones he sells, including a New York-based associate he met at a gem conference who is from Myanmar and has connections at its famous Mogok ruby deposits.